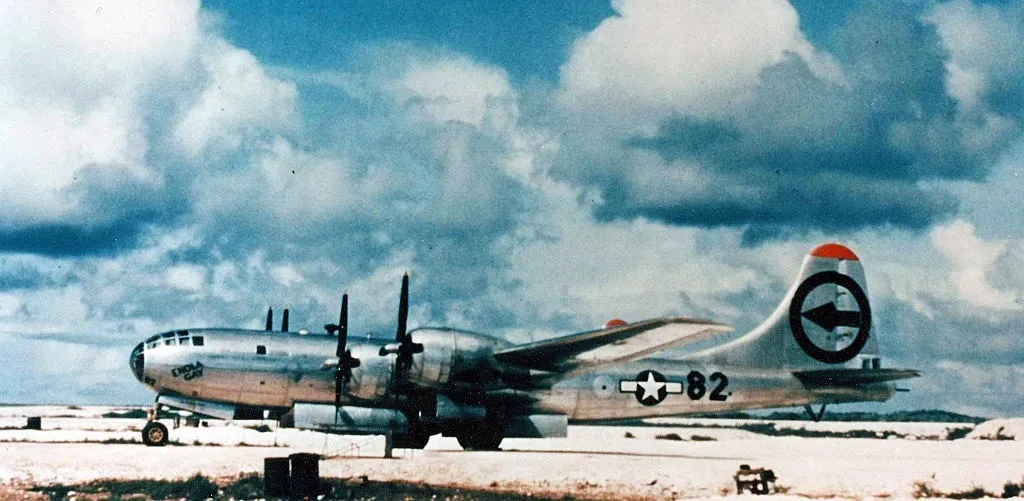

For many, the development of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress was a turning point of the Second World War. Hitting the skies in mid-1944, the bomber gave the Allies the ability to launch more effective air raids against the Japanese, giving them a leg up in the Pacific Theater. One such B-29, Enola Gay, went down in history on August 6, 1945, when it dropped the atomic bomb Little Boy over Hiroshima, marking the first time an atomic munition had been deployed in warfare.

Boeing B-29 Superfortress

The B-29 Superfortress was a game-changer in aerial warfare during World War II. Featuring advancements that weren’t seen in the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress‘ design, the aircraft could fly faster, farther and for longer than its predecessor. This was aided by its Wright R-3350 turbo-supercharged engines, which gave it a top speed of 357 MPH and a service ceiling of over 31,800 feet.

Among the B-29’s most notable features was its pressurized cabin, which allowed crews to serve comfortably at high altitudes. It also had remote-controlled machine gun turrets that allowed aerial gunners to operate their weaponry from within the bomber. Speaking of armament, the aircraft was equipped with 10 Browning M2 machine guns and a 20 mm cannon, and it had the ability to hold up to 20,000 pounds on munitions, making it a formidable force.

The B-29’s capabilities made it a crucial asset for the Allies fighting in the Pacific Theater. Its longer range allowed for air raids to be conducted deep within enemy territory, resulting in the prolonged destruction of Japan’s industrial and military capabilities.

Constructing the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay

The B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay was constructed at the Glenn L. Martin Company plant in Bellevue, Nebraska. It was one of 65 built with the “Silverplate” specification, a modification program specifically tailored for atomic bombing missions. These changes included an altered bomb bay, to accommodate larger atomic munitions; the removal of most of its defensive armament, to lessen the bomber’s overall weight; and the installation of Curtiss Electric reversible-pitch propellers for better performance.

The “Silverplate” B-29s also featured enhanced engines with fuel injection and improved cooling systems, which were crucial for long-range missions.

Enola Gay, serial number 44-86292, was accepted by the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) in May 1945. It was assigned to the 393rd Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), 509th Composite Group.

Early service in the Pacific Theater

The B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay saw service in the Pacific Theater, primarily operating out of North Field, Tinian. Before its mission over Hiroshima, the aircraft participated in several training flights and bombing missions. It was initially assigned the Victor number 12, but this was later changed to Victor 82, to avoid misidentification.

In July 1945, Enola Gay conducted eight practice flights and two combat missions, dropping conventional pumpkin bombs on industrial targets in Kobe and Nagoya, Japan.

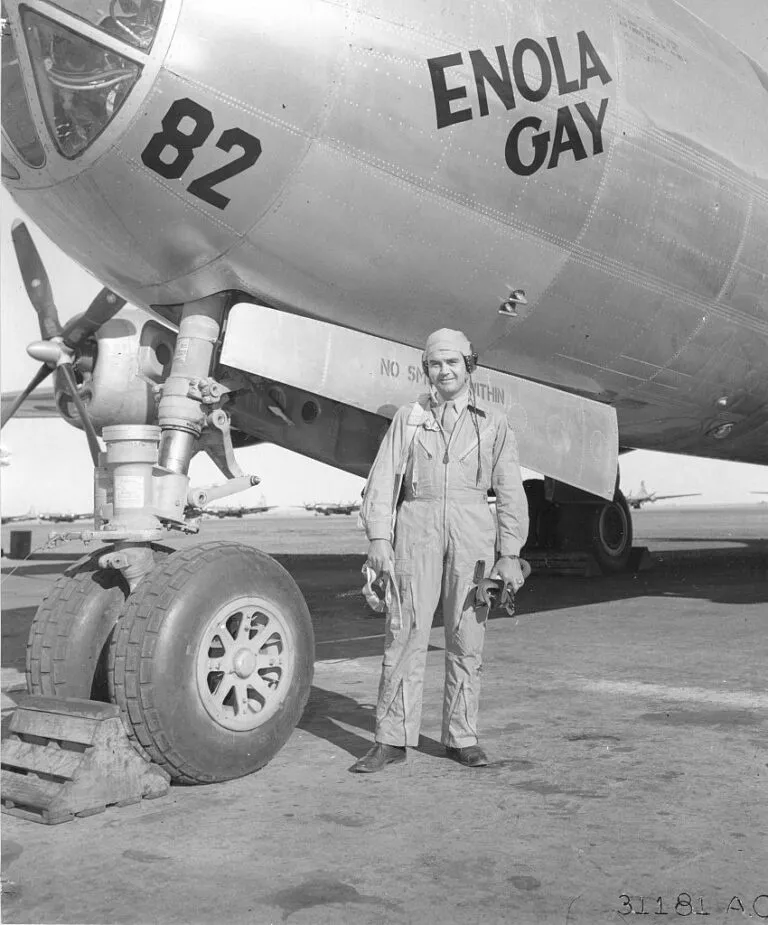

Paul Tibbets personally chose the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay

Col. Paul Tibbets, commander of the 509th Composite Group, was a seasoned aviator with experience flying the B-17 Flying Fortress over Europe. He was handpicked to lead the group, thanks to his exceptional skills and leadership qualities.

Tibbets personally selected the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay for the upcoming mission over Hiroshima and named it after his mother, Enola Gay Tibbets, as a tribute to her influence and support throughout his life. The name was painted on the aircraft just before the historic flight.

One of the notable early missions undertaken by Enola Gay occurred on July 31, 1945, when it participated in a rehearsal flight for the upcoming atomic bombing operation. This was crucial in ensuring the success of the mission, as it allowed the bomber’s crew to familiarize themselves with the specific procedures and challenges they would face.

Atomic bombing of Hiroshima

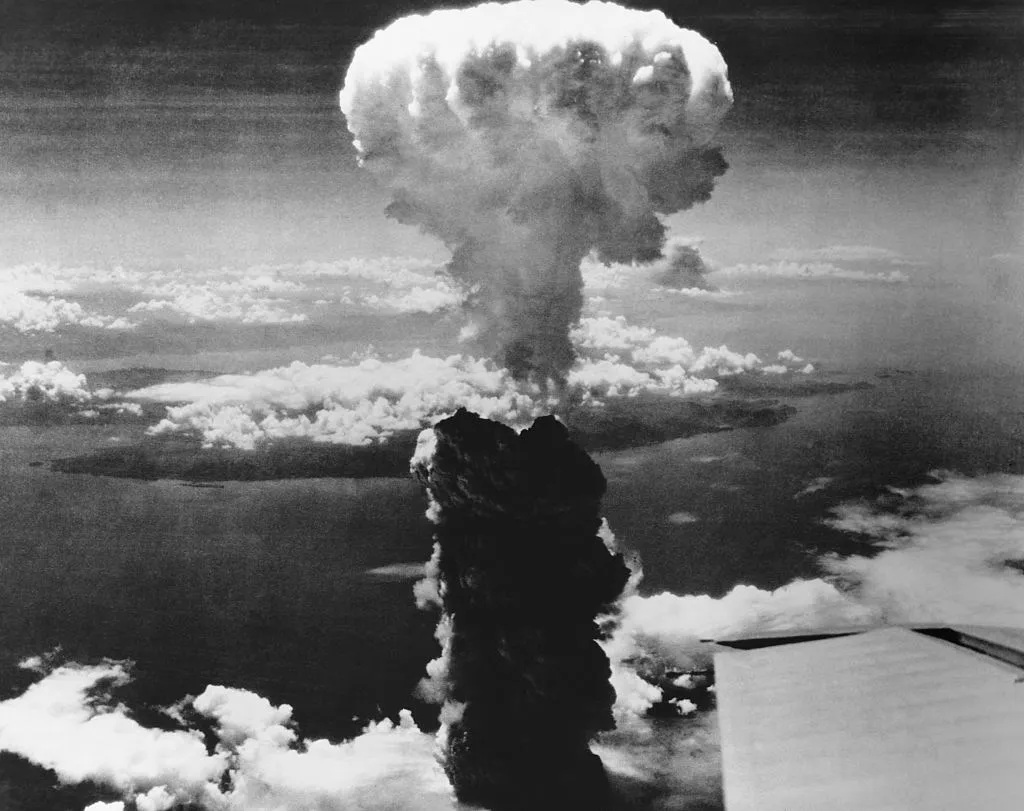

On August 6, 1945, the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay took off from North Field, carrying the atomic bomb codenamed Little Boy. The mission was meticulously planned, with Hiroshima named the primary target and Kokura and Nagasaki serving as secondary ones. The bomber was accompanied by two other B-29s: The Great Artiste, carrying instrumentation, and Necessary Evil, tasked with photographic documentation.

At 8:15 AM, Enola Gay dropped Little Boy from an altitude of 31,060 feet. The bomb detonated approximately 1,968 feet above the city, unleashing a blast equivalent to 15 kilotons of TNT. The impact was devastating, creating a firestorm that fully engulfed Hiroshima. Enola Gay‘s crew even felt the shockwaves as they flew 11.5 miles away.

The explosion destroyed nearly 70 percent of Hiroshima’s buildings and caused an estimated 70,000-80,000 immediate deaths, with tens of thousands more succumbing to injuries and radiation exposure in the following months. The mission was deemed a success from a military standpoint, but it also marked the beginning of a new and terrifying era in warfare.

Atomic bombing of Nagasaki

Three days after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, on August 9, 1945, another munition was dropped, this time on Nagasaki. While the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay didn’t carry the bomb this time around, it did play an important role as the weather reconnaissance aircraft for the original target, Kokura.

The B-29 Bockscar, piloted by Maj. Charles W. Sweeney, carried Fat Man, with the intention of dropping it on Kokura. However, poor visibility meant the mission was diverted to Nagasaki. Enola Gay had reported clear skies over the former, but, by the time Bockscar arrived, the city was obscured by smoke from bombings that had taken place days prior.

After three unsuccessful passes, Bockscar flew to Nagasaki and successfully dropped Fat Man. The detonation led the deaths of an estimated 40,000-70,000 people. Despite being tactically challenging, the mission ultimately achieved its objective.

What happened to the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay?

After World War II, the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay returned to the United States and was stationed at Roswell Army Air Field, New Mexico. In May 1946, it was flown to Kwajalein Atoll for Operation Crossroads, but it didn’t participate in the drops at Bikini Atoll.

The decision to preserve Enola Gay was made in 1946, at which point the aircraft was moved to Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona, for storage. On August 30, it was officially transferred to the Smithsonian Institution. Over the new few years, the bomber was moved to various locations, before being disassembled and stored at the Smithsonian’s facility in Suitland, Maryland.

Controversy surrounding a planned exhibit

The B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay‘s later history was fraught with controversy. In the 1980s, veterans’ groups began lobbying for the aircraft to be restored and exhibited, leading to a debate regarding how to present the bomber, given its involvement in the atomic bombings of Japan. The Smithsonian had planned an exhibit for the 50th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing, but this sparked further controversy, due to its focus on the Japanese casualties and the ethical implications of using atomic weapons.

The exhibit, called The Crossroads: The End of World War II, the Atomic Bomb and the Cold War, faced backlash from various groups who felt it didn’t represent the American perspective. This controversy culminated in the resignation of National Air and Space Museum Director Martin O. Harwit and the cancellation of the original exhibit.

A revised, less controversial version was subsequently displayed, focusing more on the technical aspects of the aircraft.

Where can you view the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay today?

Restoration work on the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay took years, with 300,000 staff hours put into the project. The aircraft was subsequently shipped in parts to its new home in Chantilly, Virginia, where it was reassembled and displayed in December 2003.

Leave a Reply